The National Institute of Standards and Technology (“NIST”), part of the Dept of Commerce, has been at the forefront of federal cyber and information security efforts, issuing numerous “Special Publications” addressing cyber and data security issues, risk management, encryption, mobile security and related topics. It’s latest significant release on Feb. 12th of the final Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity Framework will be influential. Why? Read on…

Background. In light of perceived cyber “infrastructure” security gaps and Congressional intransigence in passing legislation to address the issue, the Obama Administration a year ago on Feb 12, 2013 issued Executive Order 13636, Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity (the “EO”), which mandated via Sec. 7 that NIST:

“lead the development of a framework to reduce cyber risks to critical infrastructure (the ‘Cybersecurity Framework’). The Cybersecurity Framework shall include a set of standards, methodologies, procedures, and processes that align policy, business, and technological approaches to address cyber risks. The Cybersecurity Framework shall incorporate voluntary consensus standards and industry best practices to the fullest extent possible measures.”

Exactly a year later, NIST has released the final first Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity (“Framework”). The road to the this Version 1.0 final release came only after a long process in which NIST issued multiple framework drafts and held formal workshops as well as numerous informal weekly call-in sessions. NIST further received over 200 submitted public comments to its October 29, 2013 Preliminary Cybersecurity Framework, which incorporated a controversial “Appendix B” that included specific privacy provisions many, including myself, felt were slip-streaming “privacy” recommendations into a document ostensibly designed to address data and information security. Given the public comments opposing the privacy aspects NIST eliminated Appendix B as it previously stood in the final Framework stating “the methodology did not reflect consensus private sector practices and therefore might limit use of the Framework.”

Who Needs to Pay Attention? The Framework is targeted toward hardening and safeguarding the cyber security of “critical infrastructure,” defined in the EO as both physical or virtual infrastructure so “vital to the United States that the incapacity or destruction of such systems and assets would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination of those matters.”

In turn the EO directed the Department of Homeland Security to identify critical infrastructure and industries. The list the DHS compiled identifies including chemical plants, telecommunications providers, water supply facilities; defense components, energy and utilities (including nuclear facilities), food and agriculture, healthcare and waste management facilities among others.

It should be stressed, as the Framework itself notes, the guidance and recommendations provided are “voluntary.” The goal of the Framework and the EO at present is a “voluntary program to support the adoption of the Cybersecurity Framework by owners and operators of critical infrastructure and any other interested entities.”

While none of the Framework’s recommendation or guidance are mandated by law or enabling regulations, why should anyone care (in the sense that non-compliance, at this point, carries no penalty)? Indeed the Framework states in its 1.0 incarnation it “is a living document and will continue to be updated and improved as industry provides feedback on implementation.”

While this posture may change in the future, at the moment the White House is developing various “carrots” as incentives for companies to speed adoption, such as potentially providing cybersecurity insurance (which the federal government is increasing promoting), federal grants, technical assistance, possible liability limitation (although this would require Congressional action), rate recovery consideration for regulated utilities and industries and sharing of cybersecurity research.

But despite its present “voluntary” nature the Framework (and future iterations) will be influential. Why?

- For the federal government and government agencies the Framework will likely become an “effective” mandate for vendors and contractors in specifying and reviewing cyber security through governmental procurement and contracting efforts. In short, if you do business with or provide services to federal agencies you should expect the Framework’s recommendations to become part of federal cyber-risk management via procurement efforts.

- Additionally I expect the Framework to ultimately become a baseline “best practice” and therefore may be incorporated by reference in numerous private contracts that specify service providers will utilize industry best practices in their cybersecurity efforts.

- Finally, the plaintiff’s bar are eagerly waiting no doubt to argue that failure to comport with the Framework for at lease “critical cyber infrastructure” parties is evidence of negligence. In connection defense counsel will need to ascertain how to respond to the Framework in its “legal defensibility” analysis.

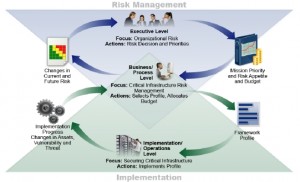

We’ll be detailing the Framework’s three part components – the Framework Core, the Framework Profile and the Framework Implementation Tiers – in future posts (and will be conducting a LSI Telebriefing on the Framework in the near future). Until then there are several key takeaways to consider.

We’ll be detailing the Framework’s three part components – the Framework Core, the Framework Profile and the Framework Implementation Tiers – in future posts (and will be conducting a LSI Telebriefing on the Framework in the near future). Until then there are several key takeaways to consider.

Key Takeaways

- Critical Infrastructure players should begin assessment of existing cyber security practices, policies and programs in light of the Framework and consider incorporation of components as they make business and security sense in ongoing cybersecurity reviews and updates.

- Vendors, contractors and service providers to critical infrastructure players should expect to see Framework recommendations appearing in security schedules and associated contractual requirements as CI players flow the Framework’s recommendations downstream. What may be voluntary for critical infrastructure parties may not be so “voluntary” for their vendors in turn. As a result, gaining familiarity with the Framework should be on a short list of cybersecurity “todos.”

- The EO giving rise to the Framework focused (controversially) on sharing cyber security information among participants. The Framework isn’t directed toward this prong of the EO, but will likely form a platform for any such “discussion items” and shared focus points.

- Big data is at odds with limited data collection and sharing of PII. When it comes to cybersecurity less collection is often more. However, the rise of “Big Data” uses (or more properly label in my opinion “Big Connections”) is at odds with the principles of limited data collection. The deletion of Appendix B, while the right choice in context of the Framework’s goals, should not diminish any steps taken to improve cybersecurity that may also be used to improve privacy and data security of PII.

To discuss the Framework, how it may impact or effect your business ventures or operations, feel free to contact us at 203 307-2665 or info@SmartedgeLawGroup.com